Literature and Publishing

South Asians have been reshaping Britain’s literary culture for over a century, influencing the publishing scene and pushing for their inclusion at its centre, as well as authoring a wide range of novels, short fiction and poetry

Overview

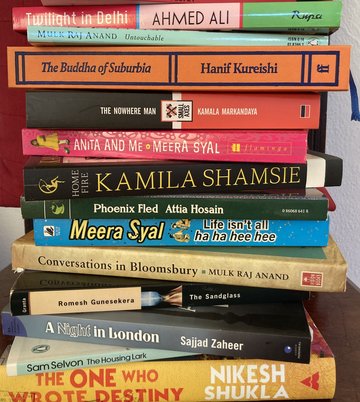

In the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Indian travellers wrote accounts of their experiences of Britain. Some of these, including by Mirza Abu Talib Khan and Mirza Itesa Modeen, were translated into English and published in Britain in the early nineteenth century. Such travellers’ accounts continued through the nineteenth century; Parsee journalist Behramji Malabari’s 1893 The Indian Eye on English Life, published in London by Archibald Constable & Co., is a notable example. Indians also played a significant role in the literary culture that characterized London’s Bloomsbury in the inter-war years of the twentieth century. Mulk Raj Anand worked as an editor for Hogarth Press and The Criterion magazine, as well as publishing his first novel, Untouchable, with Wishart in 1935. In the same year, Anand, along with Sajjad Zaheer and others, established in London the Progressive Writers’ Association – which, as the All-India Progressive Writers’ Association, went on to campaign for independence and social equality through writing in India. In 1939 Sri Lankan poet M. J. Tambimuttu launched the literary journal Poetry London, which featured work by a number of the most influential poets.

While the vast majority of this generation of writers returned to South Asia, a later generation stayed, making Britain their home. This includes Attia Hosain, who arrived in 1947, and Kamala Markandaya, who arrived soon after and went on to write a number of novels, including The Nowhere Man (1972), an early example of a South Asian-authored novel based in Britain. In 1981 Salman Rushdie became the second South Asian writer (after Indian Trinidadian V. S. Naipaul) to win the Booker Prize with his novel Midnight’s Children, which went on to win the Best of the Booker Prize twice, in 1993 and 2008, making him one of the most highly acclaimed novelists of our times, as well as one of the most controversial, owing to the 1989 fatwa calling for his assassination. It was also in the 1980s that South Asian British writers began to intervene in a more politically conscious manner, aware of the marginalization of racialized writers in literary culture. Founded in 1984 by Ravinder Randhawa, the Asian Women’s Writers’ Collective sought to nurture and promote creative writing by Asian women. While the organization folded in 1997, it provided a platform for Randhawa, as well as fellow members Rukhsana Ahmad and Meera Syal, to publish novels of their own.

The following two decades saw the establishment of what we might call ‘British Asian writing’ – a body of work that is set in Britain and speaks especially to the experiences of a burgeoning second generation. Hanif Kureishi’s landmark novel The Buddha of Suburbia, published by Faber in 1990, followed his success as a screenwriter for the films My Beautiful Laundrette (1985) and Sammy and Rosie Get Laid (1987); while poets Moniza Alvi and Imtiaz Dharker inaugurated their long careers with their first collections in 1993 and 1989, respectively. In 2003 Monica Ali’s novel Brick Lane garnered critical and commercial acclaim, as well as some controversy, and, in the wake of the 9/11 and 7/7 terror attacks, a wave of authors of Pakistani heritage penned successful novels, including Nadeem Aslam and Kamila Shamsie. The contemporary period has seen a renewal of literary activism among writers of colour. Nikesh Shukla, among others, has opened up opportunities for more South Asian British writers to make their mark on British culture, while initiatives such as the Jhalak Prize have helped to enhance their profiles. British Asian writers have expanded into genre fiction, seeing success as crime novelists (for example, Kia Abdullah) as well as with romance (Ayisha Malik); and women’s collectives, such as The Whole Kahani, continue to drive literary change.

Another interesting thing

In 1935, activist and lawyer V. K. Krishna Menon established Pelican Books, the non-fiction, educational imprint of Penguin Books – an early example of a South Asian making their mark on a publishing industry whose lack of racial diversity has been spotlighted in the twenty-first century.

Browse this theme

Image credit

Photo taken for 'South Asian Britain' (2025)