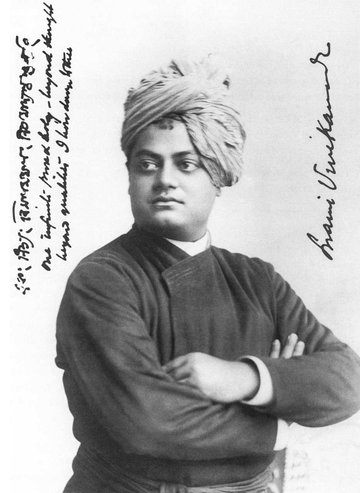

Swami Vivekananda

‐

Spiritual leader and teacher

Other names

Narendranath Dutta

Place of birth

Place of death

Calcutta, India

Date of time spent in Britain

1895, 1896

About

Swami Vivekananda was a charismatic Indian spiritual leader, founder of the Ramakrishna Mission in Calcutta and a primary interpreter of Vedantic thought (non-dualist Hinduism) to the West. Though it was never his primary intention, he became a forerunner in opening the spiritual channels of connection between Britain and India that would draw disciples in both directions in the interests of further religious study, pilgrimage, fundraising and proselytizing the guru Sri Ramakrishna’s message. Margaret Noble, or Sister Nivedita, and the American Josephine Bull were among his foremost followers. His vigorous opposition to caste oppression probably exerted some influence on the development of M. K. Gandhi’s thought.

Born into a middle-class Bengali family, Narendra Dutta’s education initially took him on a secular path. An anti-orthodox thinker from an early age, though a spiritual seeker, he studied western philosophy and European history first at Presidency College, Calcutta (from 1879) and then at the Scottish Church College. Already at this stage he believed that India required scientific and technological modernization in order to achieve self-realization and escape the social stagnation of generations. Later, this belief in national masculinization through science would assume a spiritual aspect: modernization would represent the rediscovery of India’s soul in all its fullness.

As a student Narendra Dutta expressed some interest in Keshub Chunder Sen’s Brahmo Samaj, but in 1881 he fell under the powerful influence of the Swami Ramakrishna Paramahamsa of the Kali temple, Calcutta, whose successor he became after the latter’s death in 1886. In 1890 he set out on a journey across India, in order to get to know his country, and it was while engaged in this quest that the name Vivekananda was bestowed upon him.

International acclaim followed his dynamic lecture on Hinduism at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. His theme, the Unity of the Divine, chimed with and stimulated growing interest in the West in what was now increasingly termed world religion. His many talks, speeches and seminars given in England and America on his 1895–6 tour were significant to many in pointing a way beyond the social and cultural borderlines which colonial times had embedded.

In 1897 Vivekananda founded the Ramakrishna Mission at Belur. In 1893 he had met the industrialist Sir Jamshetji Tata, who now tried to persuade him to head the Research Institute of Science he had founded, but Vivekananda declined on religious grounds and because his tireless travel had taken a toll on his health (he suffered from diabetes and asthma). He had long predicted, accurately as it turned out, that he would die before the age of 40. His followers believed he achieved mahasamadi, conscious departure from the body at the time of death.

World Parliament of Religions, Chicago, 1893

Max Müller (met in 1896), Margaret Noble (Sister Nivedita), Sri Ramakrishna, Jamshetji Tata.

British Theosophists

Raja Yoga (1896)

Swami Vivekananda’s Complete Works, 9 vols (Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama, 2001)

Boehmer, Elleke, Empire, the National and the Postcolonial: Resistance in Interaction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002)

Nandy, Ashis, The Intimate Enemy (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1983)

Noble, Margaret, The Master as I Saw Him (London: Longman’s, 1910)

Roy, Parama, Indian Traffic: Identities in Question in Colonial and Postcolonial India (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998)

What then do I mean by the ideal of a universal religion? I do not mean any one universal philosophy, or any one universal mythology, or any one universal ritual held alike by all; for I know that this world must go on working, wheel within wheel, this intricate mass of machinery, most complex, most wonderful. What can we do then? We can make it run smoothly, we can lessen the friction, we can grease the wheels, as it were. How? By recognising the natural necessity of variation…We must learn that truth may be expressed in a hundred thousand ways.

From ‘The Ideal of a Universal Religion’, talk given in New York, 12 January 1896, and London, 4 June 1896

Image credit

Wikimedia Commons