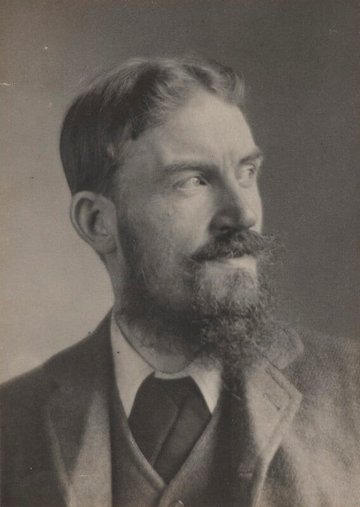

George Bernard Shaw

‐

Anglo-Irish playwright, activist and an outspoken supporter of Indian independence

Place of birth

Date of arrival to Britain

Place of death

Ayot Saint Lawrence, Hertfordshire

Date of time spent in Britain

1876–1950

About

George Bernard Shaw was an Anglo-Irish playwright and political activist. Born and schooled in Dublin, he came to England in 1876. He educated himself by reading in the British Museum, and started his writing career as a music and literary critic for several periodicals. After unsuccessful attempts at novel writing, Shaw turned to drama. He wrote over sixty plays in the course of his life, including Man and Superman (1903), Pygmalion (1912; posthumously adapted as the musical My Fair Lady) and Saint Joan (1923). He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1925.

Shaw, inspired by Henry George’s work, became a committed socialist in the 1880s. In 1884 he joined the newly formed Fabian Society, and gave lectures and wrote articles to further its causes. Shaw was also a vegetarian and supported Henry Salt’s Humanitarian League and its commitment to animal rights. During the First World War, he indefatigably campaigned for international peace and negotiation.

Shaw was an outspoken supporter of the Indian independence movement and a great admirer of Mahatma Gandhi, whom he met in 1931 in London. Gandhi was also an admirer of Shaw’s works. Shaw visited India in 1933 but the two could not meet as Gandhi was imprisoned at the time. Shaw also met Rabindranath Tagore in London in May 1913. Two of Shaw’s close female friends later went to India and devoted themselves to Indian causes: Annie Besant and the actress Florence Farr. Shaw met Besant in 1885; she asked him to introduce her to the Fabian Society and serialized Shaw’s novels The Irrational Knot and Love among Artists in her magazine Our Corner. Farr was at one time Shaw’s mistress, and Shaw frequently met W. B. Yeats at Farr’s home in London. In 1937 Shaw’s The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism, Capitalism, Sovietism and Fascism was reissued by Krishna Menon’s Pelican Books, inaugurating Penguin’s paperback list.

Mulk Raj Anand, William Archer, Max Beerbohm, Annie Besant, Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, H. N. Brailsford, Robert Bridges, G. K. Chesterton, W. H. Davies, Bonamy Dobrée, Rajani Palme Dutt, E. M. Forster, M. K. Gandhi, Henry George, Lady Gregory, Frank Harris, C. E. M. Joad, Augustus John, Jiddu Krishnamurti, John Lane, Harold Laski, T. E. Lawrence, Raymond Marriott, Eleanor Marx, V. K. Krishna Menon, Naomi Mitchison, May Morris, William Morris, Gilbert Murray, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sydney Haldane Olivier, A. R. Orage, Paul Robeson, Shapurji Saklatvala, Henry Salt, W. T. Stead, The Sitwells, Rabindranath Tagore, Ellen Terry, W. B. Yeats, Avabai Wadia, Ensor Walters, Beatrice Potter Webb, Sidney Webb, H. G. Wells, Oscar Wilde, Leonard Woolf, Virginia Woolf, Israel Zangwill.

A Manifesto, Fabian Tracts 2 (London: Standring, 1884)

Cashel Byron’s Profession (London: Modern Press, 1886)

An Unsocial Socialist (London: Sonnenschein, Lowrey, 1887)

The Quintessence of Ibsenism (London: Scott, 1891)

Widowers’ Houses (London: Henry, 1893)

Plays: Pleasant and Unpleasant, 2 vols (London: Grant Richards, 1898)

The Perfect Wagnerite: A Commentary on the Ring of the Niblungs (London: Grant Richards, 1898)

Love among the Artists (unauthorized edition, Chicago: Stone, 1900; authorized, revised edition, London: Constable, 1914)

Three Plays for Puritans (London: Grant Richards, 1901)

Man and Superman: A Comedy and a Philosophy (Westminster: Constable, 1903)

The Common Sense of Municipal Trading (Westminster: Constable, 1904)

Fabianism and the Fiscal Question: An Alternative Policy (London: Fabian Society, 1904)

The Irrational Knot (London: Constable, 1905)

Dramatic Opinions and Essays, 2 vols (London: Constable, 1907)

John Bull’s Other Island and Major Barbara, also includes How He Lied to Her Husband (London: Constable, 1907)

The Sanity of Art: An Exposure of the Current Nonsense about Artists Being Degenerate (London: New Age Press, 1908)

Press Cuttings (London: Constable, 1909)

The Doctor’s Dilemma, Getting Married, and The Shewing-Up of Blanco Posnet (London: Constable, 1911)

Misalliance, The Dark Lady of Sonnets, and Fanny’s First Play, with a Treatise on Parents and Children (London: Constable, 1914)

Common Sense about the War (London: Statesman, 1914)

Androcles and the Lion, Overruled, Pygmalion (London: Constable, 1916)

How to Settle the Irish Question (Dublin: Talbot Press; London: Constable, 1917)

Peace Conference Hints (London: Constable, 1919)

Heartbreak House, Great Catherine, and Playlets of the War (London: Constable, 1919)

Back to Methuselah: A Metabiological Pentateuch (London: Constable, 1921)

Saint Joan (London: Constable, 1924)

(with Archibald Henderson) Table-Talk of G. B. S.: Conversations on Things in General between George Bernard Shaw and His Biographer (London: Chapman & Hall, 1925)

Translations and Tomfooleries (London: Constable, 1926)

The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism and Capitalism (London: Constable, 1928); enlarged and republished as The Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism, Capitalism, Sovietism and Fascism, 2 vols (London: Penguin, 1937)

Immaturity (London: Constable, 1930)

The Apple Cart (London: Constable, 1930)

What I Really Wrote about the War (London: Constable, 1930)

Our Theatres in the Nineties (London: Constable, 1931)

Music in London, 1890–1894 (London: Constable, 1931)

The Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for God (London: Constable, 1932)

Too True to Be Good, Village Wooing & On the Rocks: Three Plays (London: Constable, 1934)

The Simpleton, The Six, and The Millionairess (London: Constable, 1936)

London Music in 1888–89 as Heard by Corno di Bassetto (Later Known as Bernard Shaw), with Some Further Autobiographical Particulars (London: Constable, 1937)

Geneva: A Fancied Page of History in Three Acts (London: Constable, 1939; enlarged, 1940)

Shaw Gives Himself Away: An Autobiographical Miscellany (Newtown, Montgomeryshire: Gregynog Press, 1939)

In Good King Charles’s Golden Days (London: Constable, 1939)

Everybody’s Political What’s What? (London: Constable, 1944)

Major Barbara: A Screen Version (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1946)

Geneva, Cymbeline Refinished, & Good King Charles (London: Constable, 1947)

Sixteen Self Sketches (London: Constable, 1949)

Buoyant Billions: A Comedy of No Manners in Prose (London: Constable, 1950)

An Unfinished Novel, ed. by Stanley Weintraub (London: Constable, 1958)

Shaw: An Autobiography, 1856–1898, compiled and ed. by Weintraub (New York: Weybright & Talley, 1969)

Shaw: An Autobiography, 1898–1950: The Playwright Years, compiled and ed. by Weintraub (London: Reinhardt, 1970)

Passion Play: A Dramatic Fragment, 1878, ed. by Jerald E. Bringle (Iowa City: University of Iowa at the Windhover Press, 1971)

The Road to Equality: Ten Unpublished Lectures and Essays, 1884–1918, ed. by Louis Crompton and Hilayne Cavanaugh (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1971)

Flyleaves, ed. by Dan H. Laurence and Daniel J. Leary (Austin, TX: W. Thomas Taylor, 1977)

Bernard Shaw: The Diaries 1885–1897, ed. by Weintraub, 2 vols (University Park and London: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1986)

Bax, Clifford (ed.) Florence Farr, Bernard Shaw and W. B. Yeats (Dublin: Cuala Press, 1941)

Dutt, Rajani Palme, George Bernard Shaw: A Memoir, and ‘The Dictatorship of the Proletariat’, the Famous 1921 Article by George Bernard Shaw (London: Labour Monthly, 1951)

Joad, C. E. M. (ed.) Shaw and Society (London: Odhams Press, 1953)

Lawrence, Dan H., Bernard Shaw: A Bibliography, 2 vols (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983)

Rao, Valli, ‘Seeking the Unknowable: Shaw in India’, Shaw 5, special issue, ‘Shaw Abroad’, ed. by Rodelle Weintraub (1985), pp. 181–209

Shah, Hiralal Amritlal, ‘Bernard Shaw in Bombay’, Shaw Bulletin 1.10 (November 1956), pp. 8–10

Manuscript Collections, British Library, St Pancras

1933–40 correspondence and papers related to ‘Political Science in America’ lecture, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries, New York

Bernard F. Burgunder Collection of George Bernard Shaw, Department of Manuscripts and Archives, Cornell University Libraries, Ithaca, New York

Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Fabian Society Archives and Bernard Shaw Collection, Archives Division, London School of Economics Library

George Bernard Shaw Collection, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin

Shaw in Bombay Extols Gandhi

BOMBAY, Jan. 8. George Bernard Shaw arrived in India for the first time today, confessing his admiration for Mahatma Gandhi as ‘a clear-headed man who occurs only once in several centuries’.

Bronzed by the Eastern sun, Mr. Shaw stood on the deck of the Empress of Britain, which is taking him on a world cruise, and gave Indian newspaper men rapid-fire opinions of the Mahatma and Indian affairs generally.

‘It is very hard for people to understand Gandhi, with the result that he gets tired of people and threatens a fast to kill himself’, Mr. Shaw said. ‘If I saw Gandhi I should say to him, “Give it up, it is not your job.”

‘The people who are the most admired are the people who kill the most. If Gandhi killed 6,000,000 people he would instantly become an important person. All this talk of disarmament is nonsense, for if people disarm they will fight with their fists.’

Referring to Mr. Gandhi’s present crusade against Untouchability, Mr. Shaw said that if an English labourer proposed to marry a duchess he would very soon find out that he was an Untouchable.

‘That gives me enough to think about without bothering to know anything about the Indian Untouchables’, said the author, with a grin.

Indian affairs, he continued, would henceforth have to be dealt with by Indians themselves.

‘In any future disputes between the Indians and British Governments India must not expect any support from other countries’, he declared. ‘From the viewpoint of population, India is the centre of the British Empire. It is quite possible that in the future, instead of India wanting to be separated from England, the time will come when England would make a desperate struggle to get separated from India.'

New York Times (9 January 1933), p. 12

Image credit

George Bernard Shaw by Frederick Henry Evans, platinum print, 1896, NPG P113

© National Portrait Gallery, London, Creative Commons, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/