British Black Panthers

‐

An offshoot of the US Black Panther Party that campaigned for the rights of communities of both African and South Asian descent under the banner of ‘political Blackness’

About

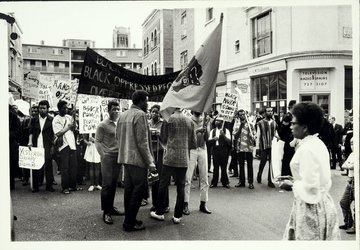

The British Black Panther Movement was founded in 1968 by Obi B. Egbuna, a Nigerian-born writer who had moved to London a few years prior; it emerged from the broader British Black Power Movement. Shortly after it was set up, Altheia Jones-LeCointe, a female student from Trinidad, assumed the leadership role to replace Egbuna, who had been arrested on the grounds of conspiracy. The British Black Panthers modelled itself on the US Black Panther Party, aligning with messages about mobilizing Black political consciousness that were coming from across the Atlantic at this time.

Specifically, the movement was inspired by a speech given by Stokely Carmichael, who came to Camden, London in 1967 to speak about his civil rights activism in the US. Interestingly, Carmichael drew attention to, and commended, the involvement of Asian activists in the Black Power Movement in the UK, and its inclusivity surrounding the term ‘Blackness’, which referred predominantly to Afro-Caribbean but also Asian communities. The Black Power Movement emerged in the context of anti-immigration rhetoric of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s British political sphere and press. For instance, the inflammatory 'Rivers of Blood' speech by Enoch Powell in 1968 captured the hostility towards non-white communities. People who had settled in the UK following patterns of post-war Commonwealth immigration were treated as ‘second-class citizens’ and suffered social, economic and political inequality. Through campaigning for change, by forceful means if necessary, the British Black Panthers challenged racial discrimination and police brutality. The movement soon grew to a membership of 3,000 strong in the 1970s.

A number of South Asian activists joined the British Black Panther Movement under Jones-LeCointe, such as the artist Vivan Sundaram and the writers Mala Sen and Farrukh Dhondy. There had previously been an alliance between the Black Power Movement in Britain and South Asian rights organizations such as the Indian Workers’ Association (IWA) (particularly under Jagmohan Joshi, who strove for unity with Black causes). Dhondy, who came to England from India in 1964 to study at the University of Cambridge, worked with the IWA and through this he became aware of the British Black Panthers at a conference in 1969. He has since explained that his initial role in the movement was to record information from the trials of the ‘Mangrove Nine’. The ‘Nine’ were arrested for protesting against abuses of power by the police at the Mangrove, a Caribbean restaurant and hotspot in Notting Hill. He was soon accepted into the ‘core’ membership of the British Black Panthers, and developed a close relationship with Darcus Howe, one of the ‘Mangrove Nine’. Members, including Dhondy, wrote for the movement’s key publication, called Freedom News, recording their experiences of everyday racism.

The movement broke up in the early 1970s, but a new collective emerged in its place, which took over the Race Today magazine. The magazine was originally started by the Institute of Race Relations in the 1960s but the influence of the British Black Panther Movement led to its transformation into a more radical publication, under the editorship of Darcus Howe.

As the first Black Panther Movement outside of the US, the British strand has been surprisingly overlooked in the history of racial justice work in the UK. The Panthers gained some public recognition with the release of Guerrilla, a Sky Atlantic television mini-series, directed by John Ridley, which dramatized the movement. It followed the relationship of two Panther leaders, one of whom was played by the South Asian actress Freida Pinto, as a gesture to the role of Mala Sen in the movement. This casting decision was controversial, given the absence of Black women in leading roles (despite their evidently central role in the history of the Black Power Movement), but surviving members of the movement have also commented on the importance of recognizing South Asian contributions to its campaign.

UK and US civil rights struggles, 1950s–1980s

Visit of Stokely Carmichael to London, 1967

'Rivers of Blood' speech, 1968

'Mangrove Nine' protest, 1970

Immigration Act 1971

Barbara Beese, Sunit Chopra, Farrukh Dhondy, Obi Egbuna, Darcus Howe, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Altheia Jones-LeCointe, Olive Morris, Vivan Sunderam.

Black Unity and Freedom Party, Bradford Black, Brixton Black Women’s Group, Institute of Race Relations, Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent (OWAAD), Race Today Collective, Southall Youth Movement.

Freedom News

Black People’s News Service

Race Today

Ambikaipaker, Mohan, Political Blackness in Multiracial Britain (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018)

Angelo, Anne-Marie, ‘The Black Panthers in London, 1967–1972: A Diasporic Struggle Navigates the Black Atlantic’, Radical History Review 103 (2009), pp. 17–35

‘The British Black Panthers’, BBC Radio 4 (26 July 2024), https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0007b0y

Bunce, Robert, ‘Darcus Howe and Britain’s Black Power Movement’, 20th and 21st Century Migrations, https://www.ourmigrationstory.org.uk/oms/darcus-howe-and-britains-black-power-movement

Dhondy, Farrukh, ‘A Migrant's Memories and Three Poems’, South Asian Diaspora Arts Archive, https://sadaa.co.uk/anthems/farrukh-dhondy

Dhondy, Farrukh, ‘Seeing Things Differently, the D Way’, The Asian Age (9 April 2017)

Hughes, Sarah, ‘The Story of the British Black Panthers through Race, Politics, Love and Power’, Guardian (9 April 2017)

Iglikowski-Broad, Vicky and Hillel, Rowena, ‘Rights, Resistance and Racism: The Story of the Mangrove Nine’, The National Archives (21 October 2015), https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/rights-resistance-racism-story-mangrove-nine/

Knight, Bryan, ‘Black Britannia: The Asian Youth Movements That Demonstrated the Potential of Anti-Racist Solidarity’, Novara Media (24 July 2020), https://novaramedia.com/2020/07/24/black-britannia-the-asian-youth-movements-demonstrated-the-potential-for-anti-racist-solidarity/

Obi, Elizabeth, Okolosie, Lola, Andrews, Kehinde and Amrani, Iman, ‘What Does Guerrilla Teach Us about the Fight for Racial Equality Today?’, Guardian (14 April 2017)

‘Photographs of the British Black Panthers headquarters’, The National Archives, https://beta.nationalarchives.gov.uk/explore-the-collection/stories/british-black-panthers-hq/

Samdani, Arsalan, ‘The Brown in Black Power: Militant South Asian Organizing in Post-War Britain’, Jamhoor (27 August 2019)

Thorne, Jack, ‘Guerrilla: A British Black Panther's View by Farrukh Dhondy (One of the Original British Black Panthers)’, Huffington Post (12 April 2017)

Wild, Rosie, ‘“Black Was the Colour of Our Fight”: The Transnational Roots of British Black Power’, in R. Kelley and S. Tuck (eds) The Other Special Relationship: Race, Rights and Riots in Britain and the United States (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), pp. 25–46

AC2015/37, British Black Panther Movement, papers including records related to splinter campaigns and movements of the African and Caribbean communities, 1967–1979, Black Cultural Archives, London

AC2014/25, Photofusion, digital oral histories and papers relating to HLF funded project 'Organized Youth', which researched the British Black Panther movement between 1968 and 1972, Black Cultural Archives, London

SCT/1/10, III. B, Newspaper Clippings, Heritage Quay, Huddersfield

IV/279/2/14/1-5, Interview with Mala Sen, ‘Do you remember Olive Morris?’ Oral History Project, Lambeth Archives, London

MS/2141, Papers of the Indian Workers’ Association, Library of Birmingham, Birmingham

For image and copyright details, please click "More Information" in the Viewer.

Image credit

Black Power Demonstration, August 1970, Records of the Metropolitan Police, MEPO 31/21, National Archives, Crown Copyright. Courtesy of the National Archives.

Entry credit

Ellen Smith