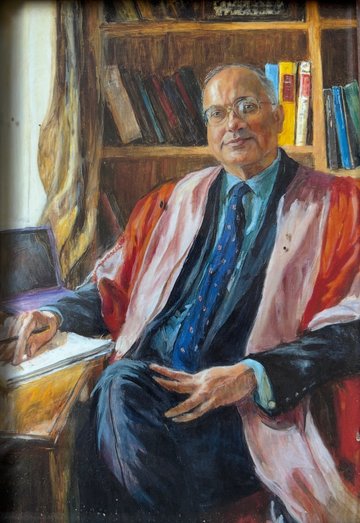

Haroon Ahmed

Haroon Ahmed, born in 1936, Calcutta (India), and died in 2024, Cambridge (England), was Professor of Microelectronics at the University of Cambridge and former Master of Corpus Christi College.

Part of the South Asian Britain oral history collection

About

The late Haroon Ahmed was Professor of Microelectronics at the University of Cambridge, as well as Life Fellow, Honorary Fellow and former Master of Corpus Christi College (2000–6). He describes his long academic career as a scientist and as the first British Pakistani Professor and Master at Cambridge, and his hope that his success will encourage other students from minority ethnic backgrounds to excel.

Haroon recounts his journey from Delhi, India, where he lived until the age of 11, to Karachi in the newly formed Pakistan in 1947, and then his move to the UK in 1954 at the age of 17. He talks about meeting his wife, Anne, of English and Scottish heritage, and of their marriage of fifty-five years. He discusses their families’ responses to a mixed marriage in the 1960s, and their lives together in Cambridge with their children. He describes shifts in his identity and in his connection to Pakistan, as well as experiences of racism and his belief in democracy and justice.

Professor Haroon Ahmed died in Cambridge on 23 October 2024.

The full interviews recorded for 'Remaking Britain', for the South Asian Britain: Connecting Histories digital resource, are available at the British Library under collection reference C2047.

Listen to Haroon talking about his experiences of racism and how cricket helped him. Please note that this clip contains a racial slur.

Interviews conducted by Maya Parmar, 5 July and 16 August 2024.

MP: And so, you have mentioned a couple of instances of racism that you experienced during this period. Do you have any other memories you'd like to share?

HA: Many. (I do, I do, I do.) There was...in 1960...’54...I arrived in this country in 1954. I don't know when your parents arrived, but in 1954 there was racism everywhere. I was beaten up on in Hammersmith because I got off the bus before a woman got off, and her husband hit me. ‘Make way for ladies, you idiot.’ So I realized, oh my God, this is a cultural thing that I should...must learn. In India, it's the other way around, you know? So, I was playing tennis in a park once, and there were in those days young men who dressed up in Edwardian clothes called Teddy boys. So, my little brother and I laughed at them, and they came and they came, and their fists were out and we were being...but the park-keeper saw us, separated us, got us on our bicycles, and away we whizzed and left the Teddy boys behind. That was almost a physical attack on us. But in the lab, it was the worst, because they would treat every other student with respect but they would tease me by calling me a bloody wog quite openly. Do you know this term? Yeah. So...and there were many instances when they wouldn't do the work. But as I said to you, this society is just amazing. I was an outstanding cricketer. So, for the department...I was playing for my college anyway, but for the department, I turned up to play. So the first year I just played, scored a lot of runs, became popular in some way because in the second year they elected me captain. And Sir John Baker was moved to come to me to say, ‘Congratulations, you're the captain of our cricket team.’ Now, that's...an election is very different from an appointment. What I learned in this country is democracy wins. You can have appointment and you have justice, but you also have democracy going along in parallel, where you favour the decision of the majority. So by the majority, I was elected captain of the team.

Listen to Haroon talking about his wife’s parents’ attitudes towards their marriage.

HA: Of course, there were still many objections to us getting married, but he changed his viewpoint, and he said afterwards, ‘I have no racism against him, I think he's the most wonderful person. The only thing I have against him, he's not a Christian.’

MP: And do you think that that was true?

HA: That was true. He was a Christian, after all. He was a vicar of Aylesford and had spent his lifetime being a cleric...being a priest. So being a priest and a Christian, and a committed Christian, and his daughter being brought up in the Christian faith, he was devastated that I wasn't a Christian. But in the end, he accepted – what could they do? There was nothing, by this time – Anne had fallen in love with me too. We were not going to be separated.

MP: And how about Anne's mother?

HA: Anne's mother was very tolerant. She was completely different. She was a racist because...it's not obvious yet she had feelings of racism because she was worried about her grandchildren being half-half and that sort of thing. But she wasn't...she was just...she liked me as a person, and she liked the fact that her daughter, for the rest of her life, was going to have a husband who would care for her immensely. And she was more conscious of that than anything else, so she was rather different. And Anne's siblings were very tolerant, very kind to me. But from time to time there were instances, moments when things did go wrong.

MP: Would you like to tell me about those?

HA: Well, they're sort of funny little incidents where, like, I had very left-wing views and her father was a very high Conservative with reading the Telegraph, and I read the Manchester...the Guardian. I've always called it the Manchester Guardian, it was then. And this clash took place. Her mother was...said something about half-breed children, something which made me very upset and angry. And...but of course, when she saw her beautiful grandchild, which is our daughter Ayesha, she's very beautiful, and she just sort of collapsed to say, 'Oh, I love my grandchildren'.

Listen to Haroon talking about being promoted to Professor and appointed Master.

HA: This was the final accolade. Nothing has given me greater pleasure than to be promoted to Professor in Cambridge. Whether it was late or not didn't matter at that time, it had happened. And I was the first person from a minority community to be made a Professor at Cambridge University. And I was thrilled that this had actually happened. I then became unaware...I became aware that the College, from the College system which is separate and it has its own status, the head of the College is called the Master, and the Master of my College, Corpus Christi College, was due to retire, and he retired, and the College wanted to elect a new master. The process is the one of election. Sixty-four fellows of the College choose somebody, often from outside, sometimes from within the College. The last Master had been an ambassador in Moscow, and had come from there to be Master. I was chosen from within the College. It was a singular honour. And I was really surprised when I got the phone call from the Senior Fellow to say that I had been selected to be Master. So, to be the Master of a Cambridge college is only known within Oxford and Cambridge what a high distinction it is.

Listen to Haroon talking about his love of Urdu poetry and English literature.

HA: So, I love poetry, both English and...so, how much do you understand, any Urdu?

MP: I do not speak Urdu, no.

HA: I'll translate it for you.

MP: Thank you.

HA: [Speaks Urdu]. What the poet is saying, ‘What pleasure does the wine giver bring?’ This is for Muslims, you know? ‘What pleasure does the wine giver bring? At the glimpse of a woman's ankle. One is a vision of paradise, the other is a glimpse of heaven.’ Isn't it beautiful? In Islamic culture, wine is forbidden, women are covered completely, only thing you can see is their ankles. 'For the pleasure of the wine giver, the glimpse of a woman's ankle, one is a vision of paradise, the other is a glimpse of heaven.' So, I love poetry and I retained that, there are Urdu poetry books, even a first course in Urdu. [Speaks Urdu]. 'These thoughts they come to me from the depths of space. I, Haroon, am merely the scribe who puts pen to paper.' So this poetry is translations of Ghalib, the great Urdu poet. And I love poetry in my native language, which I just can't lose. Can't lose that. I learned that on my mother's knee, so I remember it by heart. She taught me. But in the same way, she was educated by English governesses. She was the daughter of a very rich man, so he employed governesses to teach her at home. Because her mother died when she was just 12, so she had English governesses, English teaching. And when we were born...at 17, she was married. When we were born, she taught us English at the same time as she was teaching us Urdu. As we were learning Urdu, we were learning English. So she did us this great service, all the children. My father tried to teach us German, but it was very difficult for him to do, so we didn't do it.

MP: And so that Urdu poetry that you’re...that you’ve offered up today, is that something you've been able to share with your children and your grandchildren, and with Anne?

HA: No. No, not at all. Because it's very difficult, they don't know Urdu. And poetry is particularly difficult, the language is difficult. So, no, it's difficult, the language. I've just recited two to you, but I have many, many examples, language is extremely...even for Urdu speakers, it's cultured Urdu language. So many Urdu speakers today would not be able to understand it. You've got to be brought up as a cultured Pakistani as I was, after the age of 17, 18, 20 perhaps, and then I lost touch with my mother tongue. So, it's...I'm passionate about Urdu. I'm reading...I'm re-reading Jane Austen at the moment. And I wanted to read her again as an adult and an old man. So, it's...So, I'm proud of my heritage but I don’t want to inflict it upon my children or grandchildren. But I want them to remember their roots, that's all.

All audio and video clips and their transcriptions are excluded from creative commons licensing. This material cannot be reused or published elsewhere without prior agreement. Please address any permissions requests to: remaking-britain-project@bristol.ac.uk

Image credit

© Louise Riley-Smith. With kind permission of Louise Riley-Smith and of the Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.