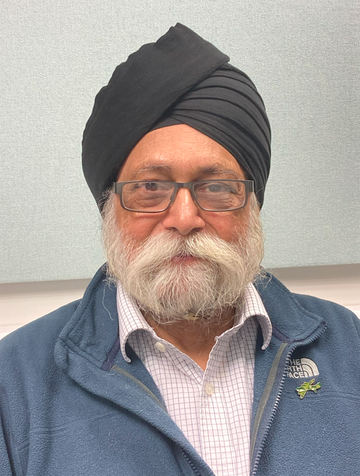

Amarjit Singh Nijjar

Amarjit Singh Nijjar was born in 1951, in the Punjab (India), and is a retired GP living in Glasgow, Scotland

Part of the South Asian Britain oral history collection

About

Amarjit worked as a GP for more than forty years in Erskine, a town outside Glasgow. He talks about his initial arrival to the UK with his mother and brother, at the age of 7, and how he found it settling into a new life in the Scottish city. Amarjit also describes his father’s experience living and working in Glasgow from 1938 as a pedlar.

Amarjit shares fond memories of joining his father on peddling ventures to nearby villages, and the kindness of his father’s customers. He also recalls times where his father would meet friends at their local cash and carries, while Amarjit would read medical books at the library. It was partly through this that Amarjit became set on being a doctor, and he talks about his experiences working as a GP in Erskine and the kindness of patients there. Amarjit also describes his own family and their identities, and describes himself as primarily Scottish, then Sikh.

The full interviews recorded for 'Remaking Britain', for the South Asian Britain: Connecting Histories digital resource, are available at the British Library under collection reference C2047.

Listen to Amarjit talking about arriving in Scotland.

Interview conducted by Rehana Ahmed, 31 January 2025.

RA: Can you tell me about your own arrival? So, you've told me a little bit about the journey, but your own arrival in Scotland, what that experience was arriving in such a different place?

ASN: Oh yes, yeah. Well, as I say, our ship docked at Southampton. My dad had already been, because you know how the ship was delayed with getting repairs in dry dock at Cape Town. My dad was up and down to Southampton by train, I don't know how many times. Because there was no mobiles then, it was only telegrams, and...so, eventually the company told him that we’d be coming in on a certain date. So, I think my dad wasn't able to come down to us, but one of our friends, he came to...his dad's friends came down to Southampton to meet us. So, when we came off the ship it was...we got a train. So, the...it was the train journey overnight from Southampton up to Glasgow. And we came into the railway station that's not there anymore in Glasgow, it was called St Enoch, which is in St Enoch Square. It was a big railway station, very grand, but it's not there. All we've got in Glasgow is Central Station and Queen Street, so St Enoch was done away with. I remember coming into St Enoch, and it was raining very heavy. And, you know, Dad was there at St Enoch waiting for us, and he had a taxi to put all...few taxis to put our stuff into, and us to...you know, for the short journey. We stayed very near St Enoch. We stayed near the city centre, so it wasn't that long. So, I remember he wouldn't let me go, and he carried me, you know, up the stairs. And I'm looking at the tenement saying, I don't know whether...where’s the sun? And the rain. It was a bit foggy that day as well. Or smog.

RA: And this was the first time your father met you?

ASN: Yes.

RA: Yeah.

Listen to Amarjit talking about his father's work as a pedlar.

RA: Did your father talk about how he was received when he knocked on people's door to sell them materials, sell them things?

ASN: When he knocked on the doors, he said that overall he was received very well. But he said that there were times when people would be abusive, you know, sort of racial abusive and even, you know, to try and assault him. But he said that was all just part of the job and they just accepted it that...you know, that they would get problems and...yeah.

RA: Were there areas where that would happen more often? Were there places that they considered to be more sort of hospitable and welcoming? For example, were there certain villages or more rural areas?

ASN: Yeah, see, I think he used to say to me that the villages were much more receptive to them than, you know, sort of larger towns. Like southern Glasgow, they would keep away from certain areas of Glasgow. My dad didn't have any customers, as they put them, you know, because Dad would call them customers. He didn't have any in Glasgow, it was all villages. So, I think he got to know where the trouble points were, and they avoided those.

RA: And who were the people who bought goods from him? Were they mainly women?

ASN: Yes, yes. Mostly women bought them. I mean, I don't really know too much about that. But sometimes during my summer holidays I would say to Dad, 'Dad, I want to come and adventure with you and see where...', you know. So he would take me. We would travel by Bluebird bus, because that's what the buses were in those days. We would travel by those into the villages. We would get off and everyone would know him, even the bus driver and things, because he was regular. And, you know, when we walked through the village everyone would be saying hello to him, and they'd come over and say hello to me and...yeah, yeah so...

RA: Did they invite him into their homes for a cup of tea or...

ASN: Yes.

RA: Yes?

ASN: Yes. A lot of...especially the older clients or customers would invite him in for a cup of tea, especially if it was very cold. He said if...on cold days, he would get tea at every house.

RA: And you showed me some of his account books...

ASN: Yeah.

RA: And told me a little bit about how he would give credit.

ASN: Yes.

RA: Can you tell me a bit more about that?

ASN: Yeah, well, I mean, he sold mostly clothes that would be very appealing to people. He said that the things that sold especially were baby clothes, especially newborn baby clothes that sold like wildfire. Everybody wanted, you know...so, he would say the...you know, the item was £1. He would give it over, he would write in the book it's Nelly, this is the date, this is her address in Cowdenbeath, £1, and then she's paid a balance of 5 shillings, so there's 15 shillings left. So he would mark down 5 paid, 15 shillings to pay. And then obviously would go back the following week, she would give him another 5 shillings. 10 shillings to pay. And then maybe Nelly would then buy something else. So there was 50 shillings to pay. And she would maybe buy a blouse for herself at a...£2. So it’d be then £2 and 50 shillings, and she would pay, say, 50 shillings, there would be £2 left. So, it continued. It continued.

RA: So, there must have been also a relationship of trust building up between him and his customers?

ASN: Yes, yes, yes. The...he said that trust was what, you know, made the...you know, that business. He said if there was no trust, you couldn't have the business then. So it was trust. And he knew that every week when he went back, the people would be there, or they would say we're on holiday next week, don't come then, come in two weeks, and we'll give you double. You know, so everyone was very nice. I remember when I went with him, I didn't go very often, but they were always nice, and they always gave me lots of sweets, and they would give me a little bit of money to buy what I wanted at the shop and...yeah.

Listen to Amarjit talking about his father tailoring tartan clothes.

RA: You've also described him as a master tailor...

ASN: Yeah.

RA: And making tartan shirts.

ASN: Yeah.

RA: When did he start? So he trained as a tailor...

ASN: Yeah.

RA: In India.

ASN: Yeah.

RA: But then when did he start making tartan shirts? And did he make them at home, or...

ASN: He made them at home. He had a machine at home. I still remember his big scissors. I couldn't pick them up, but they were huge. And he would have like Elastoplast around the handles. I used to wonder, you know, is it damaged? But it wasn't, it was to save his fingers from getting...when he was cutting the cloth. So, I think when he had established as a pedlar, and he'd stopped working at the ROF, he then found that he had time and he went back to his vocation of making tartan shirts. He made tartan trousers, made tartan jackets for people. I still remember people coming to our house. Our house was on the third floor, so we had an attic, and that's where his machine was and his cutting room. So we used to find people coming to our house, local Scottish people coming to our house to get measured up to...you know, for tartan shirts and whatever they wanted. So yeah...

RA: Amazing.

ASN: Yeah. So, I think he made a lot of money from that, because it was bespoke. I still remember there was big cars standing outside our tenement, the drivers waiting there. They would stay with the car, and the chap or the lady would come up to our house and get measured up and then come back for a fitting.

Listen to Amarjit talking about how his Sikh faith has shaped his work as a GP.

ASN: I enjoyed practice, it was an honour to practise in Erskine, which is a new town just very near Paisley on the riverbanks, banks of the River Clyde.

RA: Was that the first practice that you worked at? And did that remain your practice?

ASN: That was the first practice that I worked at, you know, as a partner. And it remained my practice for forty-three years until I retired.

RA: Can you tell me more about your work as a GP?

ASN: As I say, I always felt that my work was a service. In Sikhism, one of the tenets is to serve mankind. And in fact, my mum and also one of our holy men, who I had met in 1976, had, you know, sort of said to me, okay, you've become a doctor now, so the doctor bit is to do seva. Seva is service...you know, a service. They said, it's not for you to fill your pockets. So again, this holy man said to me, we don't want you to do private practice, because the poor man gets left behind, and you're there to treat the downtrodden. So that was that.

All audio and video clips and their transcriptions are excluded from creative commons licensing. This material cannot be reused or published elsewhere without prior agreement. Please address any permissions requests to: remaking-britain-project@bristol.ac.uk

For image and copyright details, please click "More Information" in the Viewer.

Entry credit

Zareena Pundole